(Video) Beethoven op. 81a, mvt. 2

Important Stats:

Piece: Piano Sonata op. 81a, Movement II “Abwesenheit”

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Performer: Me! (Mike Truesdell)

Audio engineer:Michael Caporizzo (faculty at Ithaca College!)

Video: Four/Ten Media

Performance clothing: NOT by Jenny Lai

Things about the piece as a whole

Historical context

Beethoven scratched out the dedication to Napoleon in his Third Symphony.

There sure was quite the falling out between Beethoven and Napoleon! Initially, Beethoven saw Napoleon as a savior of the democracy. Yet, by 1804 he had scratched Napoleon’s dedication from the title page of the Eroica symphony and soon witnessed the feeling of the power-hungry armies first-hand.

In 1809, Napoleon’s Kingdom of Westphalia centered itself in Kassel (Germany), a city where Beethoven intended to move if it weren’t for the mass convincing of aristocracy, friends, and Archduke Rudolph, who convinced Beethoven to stay with ceremonial titles, stipend and promises of future work as a composer, conductor, teacher and performer.

Personal intermezzo with no conclusion:

I’m conflicted about the nature of the relationship between Archduke Rudolph and Beethoven. On one side, it seems like a close “bromance”, which includes private lessons and dedications of some of the great later works in Beethoven’s life: “Hammerklavier” Sonata, op. 106, Piano Sonata op. 11, Grosse Fuga (both versions), the Missa Solemnis, as well as the Piano Sonata op. 81a. In his sketchbook, Beethoven dedicated op. 81a to Rudolph, writing “aus dem Herzen geschrieben” (“written from the heart”), but he delivered the piece with a more straight-laced “…on the departure of His Imperial Highness the esteemed Archduke Rudolph”.

It seems like they were close, but it is difficult to know the root of their friendship because of the power dynamic. I genuinely feel that people can be friends with their bosses/patrons, but a power dynamic between two people always muddies the water. I don’t get the impression that Beethoven was just a joyful bubbly optimist who is fueled by helping amateur rich guys live out their cultured lifestyle through composition lessons. Can you imagine Beethoven volunteering for this work? I can’t. I don’t know if this leads me to any productive place in my understanding of this piece, but I am curious about the undercurrents of these two men’s paths crossing for a few years in the early 19th century.

Ok, back to the program.

On April 9, 1809, Austria declared war on France. As the bombs fell in Vienna, Beethoven’s sensitive ears relegated him to the cellar, where he covered his ears with pillows. The psychological and physical toll that this must have taken on Beethoven is immense.

In April, Napoleon had his sights set on Vienna and was rabid with unchecked power. Aristocracy was not safe anywhere, and there was a target on Archduke Rudolph and his extended family. On May 4, 1809, Rudolph fled Vienna, and on that day, Beethoven gifted him with the first movement of what would eventually become Piano Sonata op. 81a. The other two movements, completing the sonata, were given to Rudolph upon his return in January 1810.

The instrument:

As far as I’ve read, Beethoven owned an extended-range Érard at the time that he was composing this sonata. The Érard pianos were manufactured until the 1790s and were a mere five octaves, but as the technology and compositions allowed, the ranges were slowly expanding. The extra notes allowed for a few more expressive notes in his pieces, including the extra notes in opp. 53 and 57. In op. 81a, however, this extended-range instrument did not have the low E1 for which he asked in m. 28…what’s he up to here?

It is possible that Beethoven was able to write on pianos that he didn’t own, or that he had pianos sent to him and removed without any trace or documentation. But it seems that he had this Érard from 1803 until 1825 when the piano was given to his brother, and Ludwig got a new Graf (after the Broadwood in 1817)!

He wasn’t pleased with this mahogany-cased Érard, but it did have a few extra colorful pedals, including a “lute” pedal that slipped pieces of leather between the hammers and the strings, and a “dampening” pedal that inserted cloth. There is no reason to believe that Beethoven wanted either of those pedals to be used for any of the op. 81a movements, however. But I’ll bet they were fun to play with!

If you want to explore a lot more, including fact-checking what I wrote above, explore the Orpheus Intituut’s page about Beethoven’s French Piano!

FAQ’s

So when did he compose the other two movements?

Probably toward the end of 1809. An armistice was signed on July 11, so it was presumably possible for Beethoven to get back to work on those other two movements in the summer of 1809. We are confident that he didn’t do much composing during the bombardment. He wrote to his publisher Breitkopf and Härtel: “Since 4 May I have brought into the world little coherent work, not much more than just a fragment here and there. The whole situation has affected my life and soul…”

Was op. 81a conceived all at once or in pieces?

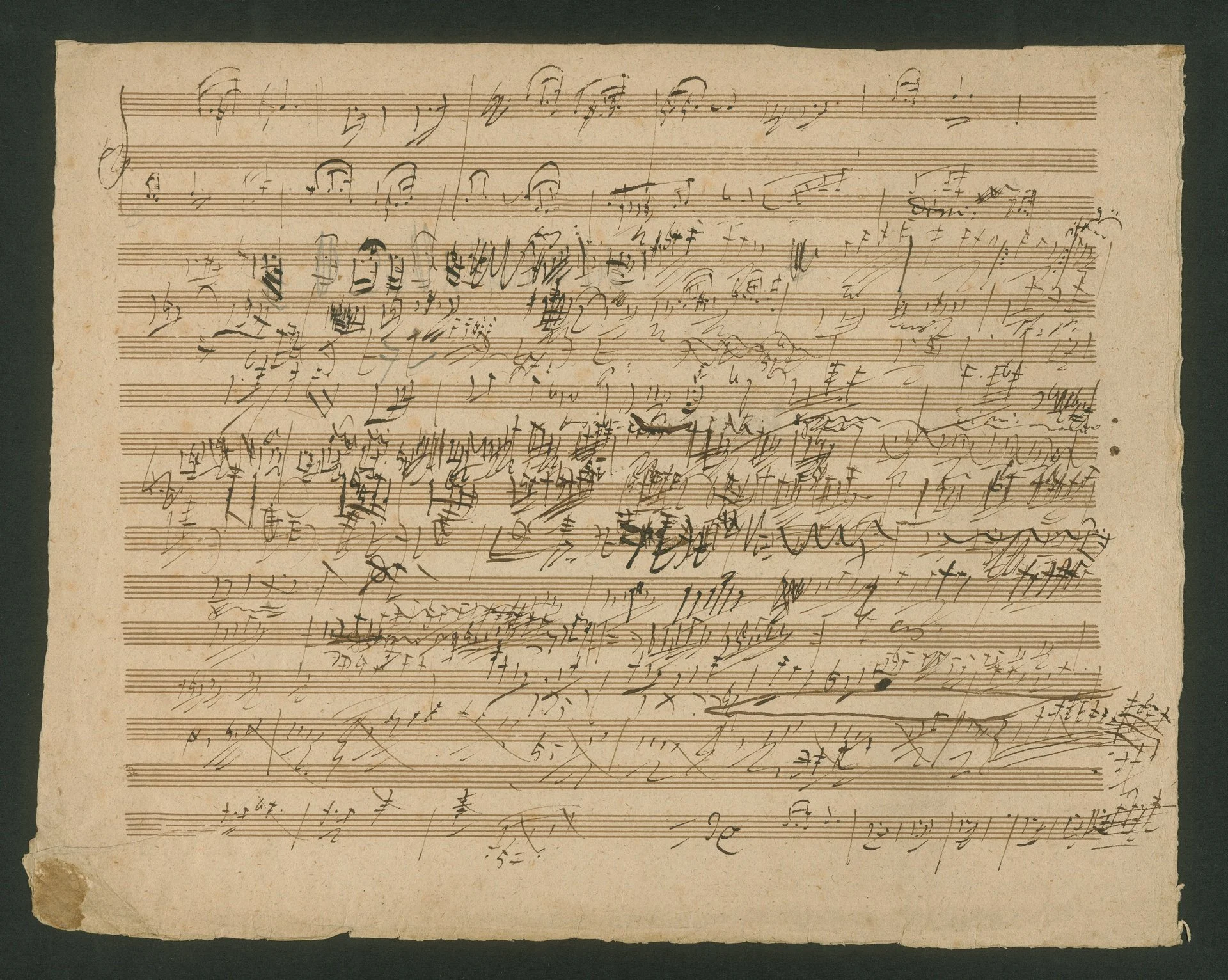

This is a sketch for op. 81a…have fun deciphering!

Barry Cooper’s The Creation of Beethoven’s 35 Piano Sonatas noted that, once Beethoven had finished sketching a first movement, he would sketch ideas, and occasionally structure, for the remaining movements. He didn’t do either in this case, so maybe the 2nd and 3rd movements composed a few months later, were also conceived a few months later. It is very possible that Beethoven never committed the ideas to paper as well. The piece is so tight thematically, formally, and conceptually that it seems probable that he formed the whole piece at once, but the surviving evidence doesn’t support that. I guess he was a good composer.

What’s up with that title?

There are a lot of titles floating around for Herr Beethoven’s works: “Pastoral” Symphony, “Hammerklavier” and “Appassionata” Sonatas, “Archduke” trio, etc., etc. But there are only two sobriquets that were given by Beethoven himself (the rest issued by publishers): the “Pathetique” sonata, op. 13, and our sonata-in-question, op. 81a. Even though Beethoven was once reported to have said, “I have always a picture in my mind, when I am composing, and work up to it”, the pictures in his head, with these two exceptions, never made it to the page.

That is a powerful realization for me. Opus 81a represented something real for Beethoven, a piece’s construction that isn’t just about putting the puzzle pieces together. That’s not to say he wasn’t a powerful and emotional composer — quite the opposite in my view — but the emotions and feelings that he expressed were directly applied to the page.

“Beethoven was the pushiest of all composers”

One of my favorite Beethoven anecdotes isn’t from Beethoven himself but from John Cage. When I was a young doctoral candidate at The Juilliard School, we had a forum with the illustrious Pia Gilbert, who had many accolades, including close contact with both Arnold Schoenberg and John Cage. She mentioned that Cage wasn’t a fan of Beethoven because he was the “pushiest of all composers”. The whole audience laughed, and it made me wonder if that was a back-handed compliment by Cage. Beethoven could convince his audience of any emotion through his air-tight technique and hyper-sensitivity to formal structures.

So why didn’t Beethoven share more of his mental pictures with the audience?

And why did he choose to share opp. 13 and 81a with the performer?

I don’t know much about the Pathétique sonata, except that I think all pianists should study with a marimbist when learning the treacherously unidiomatic left-hand octave oscillations at the “Allegro di molto e con brio”. So I don’t feel a need to speculate more on why he titled that sonata. Feel free to check out my referenced Resources below to dive deeper, though!

With op. 81a, I feel like Beethoven was in a unique and formative time of his life. He was established, in demand, struggling with physical and psychological ailments (the Heiligenstadt Testament was written on October 6, 1802). After the quasi-betrayal by Napoleon and the attacks on a city that he had called home for 17 years, it feels like he just couldn’t keep his political views contained. He wanted the world to know that he was impacted by this narcissistic looney and perhaps even give his indirect support to others who were separated from their friends and families as well.

P.S. Have you read this article about Beethoven maybe having lead poisoning? Wild.

https://www.cnn.com/2024/05/09/world/beethoven-lead-poisoning-scn/index.html

When it all gets boiled down, aren’t we all just trying to communicate?

German vs. French

op. 81a, first movement, first measure

Beethoven wasn’t hiding his program from the score. The opening three-note horn call in the first movement is accompanied by the text “Le-be-wohl,” written directly over the notes. Subsequent movements have German and French titles as well: mvt. II is “Abwesentheit (L’Absence)” (Absence) and “Das Wiedersehen (Le Retour)” (the return) before mvt. III. Additionally, there are the traditional Italian tempo markings (Adagio, Andante espressivo, and Vivacissimamente, respectively) but also German commentary as well. In the second movement, he writes: “In gehender Bewegung, doch mit viel Ausdruck” (moving and walking, but with much expression).

“Les Adieux”

The piece, op. 81a is known by music folks as the “Les Adieux” sonata, even though Beethoven was adamant that the French AND German titles be included in the publication. He even specified “certainly not in French only.” 😬 Uh oh.

However, after Breitkopf originally heeded the instructions of the composer, subsequent publications shortened the title to only French (or only German) text. Beethoven was not pleased. “I have just receved Das Lebewohl, etc. I see that you really have other copies with French titles. But why?…”

Why is he getting his undies in a bundle over this? Does he strive to showcase his linguistic prowess? Rise to the elite levels of wordsmiths and get his star on the Bilingual Thesaurus of Fame? Not really. After the quoted segment above to his publishers, he clarifies the subtle difference between his translation of each word. “Lebewohl is something very different from Les Adieux; the first is said in a hearty manner to a single person, the other to a whole assembly, to whole towns.”

“Lebewohl is something very different from Les Adieux; the first is said in a hearty manner to a single person, the other to a whole assembly, to whole towns.”

Why the weird opus number?

The splitting of an opus number is not unique in Beethoven’s output, but it is rare. He has a few sub-opus letters (i.e. opp. 72, 72a, 72b) that are different versions of the primary opus number, but only opp. 81a/b and 121a/b are the only opuses that do not have an un-lettered primary version. Is that confusing enough? Basically, I’m saying that there is an opus 81a and 81b, but no opus 81. Strange, right?

Beethoven’s sub-opus catalog

Here’s what happened: many of Beethoven’s works were published by the Leipzig publisher Breitkopf & Härtel, including opp. 75-85 between 1810-1812. Through that process, they had assigned op. 81 to the sextet for strings and two horns. Beethoven, unwilling to break the chronology, decided to split up op. 81 into 81a and 81b. Now you know.

Why does this piece matter?

Now I don’t want to presume that op. 81a is making the impact of the 9th Symphony here. But I do feel that the addition of the German characters and the “Lebewohl” title does make it a bit more sparkly than some other pieces in the 722-piece oeuvre.

The title, to me, shows a composer who is communicating to the audience in a rarely seen way. I feel that Beethoven was always an expressive composer, who was able to concisely articulate emotion quite clearly, but not specific emotion. A loud section could express anger or turmoil confusion exuberance or elation, and no matter what the listeners have a hard time connecting with emotion if we don’t know the general origin. By including the title, he focuses on our interpretation of these melodies, motives, harmonies, forms, and textures.

I feel that he wanted us to focus our interpretation of these emotions, and the audiences at the time would know even more specifically that the “Absence” was related to the Napoleonic raze through Europe. This makes the piece emotional, but also political. Kind of a “look at what this loser is doing to us!” piece.

Additionally, we find the German performance-character explanations before movements 2 and 3, in contrast to the traditional Italian. Perhaps showing a desire to communicate to his German-speaking audience more clearly, but also perhaps a small display of his nationalism. Nothing brings nationalism out of a country like tragedy!

I’m reminded of Bach’s suite movement titles — sometimes in Italian and sometimes in French — depending on the compositional style of the movement (i.e. “Corrente” vs. “Courante”). I don’t believe Beethoven was thinking about composing in anything but his own, developing, style, but it does show Beethoven using all the expressive tools at his disposal to communicate his idea to the performer and audience.

Overall, I see this piece showing Beethoven, in a time of strife and anxiety, turning his mind to his German-speaking brethren and amplifying his nationalism. I don’t believe it was a lightning bolt epiphany piece that shifted space and time, but perhaps more of a milestone on the road toward a deeper understanding of himself and the development of his craft.

My thoughts about the second movement

Why this piece?

Why just mvt. 2?

For those of you who follow my work (Hi Mom!), you may remember a video that I created, along with FourTen Media and audio engineer Rebecca Moore, of Juri Seo’s masterful vibraphone solo, v. The vigor with which I learned Seo’s piece was surprising to me. I felt a strong connection with the techniques and motivations behind her solo, and wrote (too much) about it here.

The cornerstone movement of Seo’s solo is directly influenced by op. 81a, mvt. 2, and is directly cited in Seo’s score.

As a footnote in the score, Seo writes in the score: “*’Absence,’ L.v. Beethoven, Piano Sonata op. 81a, Mov. 2”

I jumped at the opportunity to learn more about the foundations of Seo’s v. Originally, I was planning to learn the movement just as an exercise and for supplemental knowledge when approaching Seo’s solo. But the more I got into the performance of the movement, the more I felt like a public-facing video recording would also give context to my interpretation of Seo’s score.

I will have to apologize to all those Beethoven fans out there who are mid-fit right now about my playing, my instrument, my video, the recording, or especially the choice to only play the second movement.

Why did you only record the second movement?

I can’t defend this to any diehard Beethoven-ites. Really, I’m just plain sorry. I know that the attaca transition to the third movement is one of the truly great attaca musical slingshots (only second to Rachmaninoff's 3rd concerto!).

Recognizing all of this, isn’t there something eerily poetic with omitting the bookending movements in a piece that explores Absence? Why do we require a return? Why must Sam and Annie find each other at the end of Sleepless in Seattle?

I mean, not to be dark or whatever, but there is something special about marinating in the absence and truly feeling those feelings. You never know what could come from the separation: a deeper knowledge of self, perhaps, or even a stronger desire for the one who is absent. Please don’t misunderstand this! I am a happy person, but emotions can be wonderful sources of motivation and change — the light and the dark ones.

There are numerous recordings of this sonata in unique and not-so-unique interpretations, hopefully, my recording can shed a different colored light on this masterwork of human expression.

Tempo

During my “day job” as a faculty member at Ithaca College, I enjoy being surrounded by wonderful faculty colleagues. Though we all run around like Mike the Headless Chicken every day, there are some serendipitous moments of repose, when we cross paths in the hallway and exchange ideas. One of our fabulous piano faculty members, Vadim Serebryany, and I had such a moment in the spring of 2024 when we discussed op. 81a. I had spent some time working on it for this recording and he was starting to prepare it for a concert over the summer.

Many formative ideas came from that discussion, but one stuck out a bit more than the others: the tempo of the second movement. Simply, he believes the second movement needs movement. He had perfect points: the movement is not Largo or Adagio, it is Andante espressivo, and even has a qualifying statement that emphasizes the need for speed.

Beethoven wrote:

In gehender Bewegung, doch mit viel Ausdruck could be translated as “in forward motion but with expression.” (Or, “use the gas, but occasionally tap the brake.”)

However, Czerny also mentioned, “The tempos of the Adagio introduction and the Andante could be more relaxed, especially the latter, while the tempos of both fast movements could be still livelier.”

the opening to movement 2. Note the Italian and German instructions above.

What am I supposed to do??

As I was preparing my realization of the movement, I listened to a boatload of recordings, simultaneously searching for the various techniques of interpreting this movement, but, embarrassingly, figuring out if there was someone who played it convincingly and also slow enough that I could justify a marimba version. I just can’t play the florid right-hand part with two mallets as fast as pianists could play it with five fingers. But I wanted to have someone validate a slow interpretation…and I found one!

Alfred Brendel is one of the iconic Beethoven interpreters of piano history, and I was lucky enough to see him at The Juilliard School when he visited in the fall of 2009. (Check out a great interview between (now YouTube sensation) Ben Laude and Mr. Brendel in November 2009. The version of 81a that I referenced most often was recorded shortly thereafter in 2010, but he recorded this sonata multiple times throughout his long artistic career.

His 2010 recording of the second movement of op. 81a blooms, sighs, reflects, longs, doubts, and elates, but starting at the low, low tempo of 44 bpm for the quarter note. Judging by my metronome, that’s deep into “Largo”, and even slower than I need to go to realize this movement on marimba. I can’t speculate why he would choose a tempo that slows, but I felt a connection to this sparse, empty tempo. I was ready to begin.

That being written, I recently had the pleasure of hearing Mr. Serebryany perform this movement, and he was true to his word. He chose a wonderful tempo, full of movement, and direction, and not without expression. I agree with the argument that this movement should have pace and direction, and perhaps Mr. Brendel is pushing the boundaries of Beethoven’s intention, but I love both chosen tempi.

The tempo I decided to record is on the slower side, for sure, but still faster than Brendel. I have not played the piece publicly since talking with Vadim, but I would love to invite a quicker tempo into my performance and feel the new direction it creates.

Musical Analysis:

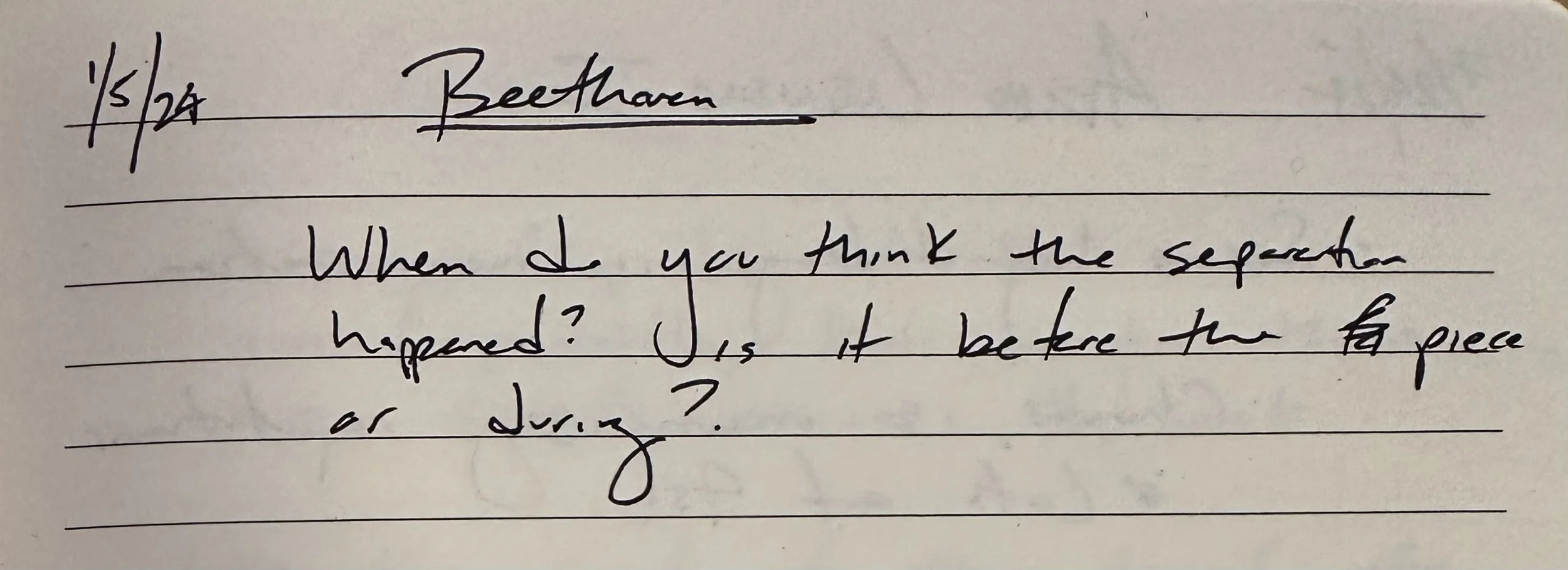

“When do you think the separation happened? Is it before the piece or during?”

This is something I wrote to myself in my practice journal during my practice process. Obviously, someone can be literal and note that Beethoven’s influence is Archduke Rudolph and he left Vienna before the movement was composed. Blah blah blah. Boring. But as an interpreter realizing this is 2024, I LOVE thinking about this question. Perhaps the opening dirge is actually just the seeds of a separation, and not the actual act itself. But if it happens during the movement, then where does it happen? Fun to think about, even if the answer seems immediately obvious to you.

movement 1 - note the dotted-16th/32nd rhythm in mm. 2-3!

In movement 2, I think we’re in C-minor at the beginning, but why is the second note in both hands an F#? It seems that we can’t even confirm our home key without sliding toward G (probably G-minor). Eventually, the m. 4 cadence in G-major feels half-cadency, so we know harmonically where we are. But immediately in m. 5, we’re doing the same elusive harmonic dance, as we cadence back in C-minor in m. 8. The non-traditional harmonic play seems an important tool that Beethoven employs throughout this short movement.

During my learning process I was curious about the return of C major harmony in m. 31. Is it a coincidence that the parallel major of the opening is grounded as far apart in the form as possible? Measure 31 is the last cadential point before we sneak up on Eb major and the final movement. Am I reading too much into this?

note measure 15 - I think it is much more stable!

Contrast this with the more stable, fluid passages in mm. 15 and 31, where the consistency of rhythmic texture gives comfort that isn’t available when silence occupies more of the measure.

There are a lot of Beethoven’s calling cards present throughout the movement, including the foreshortening of a phrase (thank you Alfred Brendel for enlightening me to this), the grumbly bass voicings, and the use of the off-beat emphasis to unground our metric spidey-sense.

For me, the most powerful aspect of this piece is the form. It is in cavatina form (thanks Charles Rosen!), which is an exposition and recapitulation without a development section. But I think this form is more powerful than that. I think giving it a name diminishes the expressivity of the structure.

The piece is clearly in a bipartite structure, with m. 21 being the beginning of the second section. Strangely enough, we begin in the fifth measure of the phrase in the recapitulation, programmatically showing that the bygone era can never return, but musically truncating the form for a more concise delivery of the message.

Everywhere I look in this movement, I can find meaning. The double-neighbor motive in m. 1 I hear the G as home (Vienna, perhaps) and the two neighbors moving away, one only a half-step to F# and the other a full whole-step to A-natural.

What are the sfz except for unexcused regrets about something you should’ve said? The cantabile sections are those memories that were somehow perfect, yet unable to be completed more in wails and heaving sobs than song. The end of the movement is an extension of a wish, just hoping for things to be as they were, even if it is impossible.

I hope you enjoy my interpretation of this small gem of Beethoven’s output.

Mike T.

Resources

The Edition I Used:

Beethoven, Ludwig van. Piano Sonata No. 26. Munich: G. Henle Verlag, 1976.

Books:

Blom, Eric. Beethoven’s Pianoforte Sonatas Discussed. New York: Da Capo Press, 1968.

Caeyers, Jan. Beethoven, A Life. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2020.

Cooper, Barry. The Creation of Beethoven’s 35 Piano Sonatas. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2017.

Czerny, Carl. On the Proper Performance of All Beethoven’s Works for the Piano. Vienna: Universal Edition, 2008.

Drake, Kenneth. The Beethoven Piano Sonatas and the Creative Experience. New York: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Gordon, Stewart. Beethoven’s 32 Piano Sonatas: A Handbook for Performers. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Huizing, Jan Marisse. Ludwig van Beethoven: The Piano Sonatas: History, Notation, Interpretation. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021.

Newman, William. Performance Practices in Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas: An Introduction. New York: Norton, 1971.

Rosen, Charles. Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas: A Short Companion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Taub, Robert. Playing the Beethoven Piano Sonatas. Portland, OR: Amadeus, 2002.

Tovey, Donald Francis. A companion to Beethoven’s Pianoforte Sonatas. New York: AMS Press, 1976.

A valuable resource for performers

Thank you for reading! If you have any thoughts or questions, feel free to contact me by clicking below!